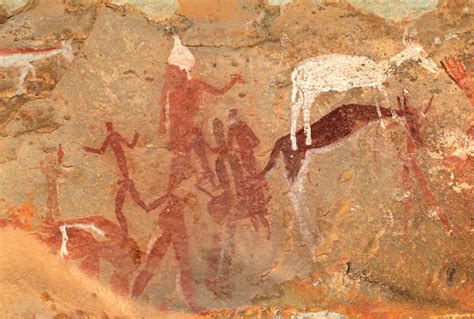

In animist traditions, such as those practiced by the Khoisan or the Xhosa for example, who settled and prayed on this Southern tip of Africa I inhabit, nature is viewed as animated and alive with spirit. Every river, tree, animal, and mountain has life-force and agency. Humans are not separate from nature; rather, they exist in a reciprocal relationship with it, shaped by mutual respect, responsibility, and acknowledgment of interconnectedness. This worldview supports practices that honour the Earth, such as rituals to ask permission from the spirits of plants and animals before hunting or harvesting, ensuring balance and respect for all forms of life.

Spirituality and respect for ancestors also play a vital role in Southern African animism. Ancestors are seen as mediators between the human world and the natural world, guiding and protecting their descendants. Through ceremony, people maintain relationships with ancestors, believing that their wisdom and presence can provide insights, blessings, and protection. In these ways, animism emphasises a holistic understanding of existence where spiritual, social, and ecological health are inseparable.

“The term animism was coined by an early anthropologist, Edward Burnett Tylor, in 1870. Tylor argued that Darwin’s ideas of evolution could be applied to human societies; he classified religions according to their level of development.

He defined animism as a belief in souls: the existence of human souls after death, but also the belief that entities Western perspectives deemed inanimate, like water, rocks and trees, and plants had souls.

Animism was, in Tylor’s view, the first stage in the evolution of religion, which developed from animism to polytheism and then to monotheism, which was the most “civilized” form of religion. From this perspective, animism was the most primitive kind of religion, while European, Protestant Christianity was seen as the most evolved of all religions.” [1]

By embracing animist traditions, without claiming they pertain to any particular religion, which tends to create polarity, we can contribute to revalorise them, overcoming these old colonial judgements of inferiority. As this worldview gets adopted more widely, we become more free to embrace gratitude for nature’s abundance and reinforce our right to connect to the environment and cultivate respect, without being judged. Animist beliefs are at the core of our humanity and do not contradict the alignment with any particular religion.

Our Western religious dominion theologies gave humans – first through Adam and Eve for example – dominion over the Earth. They set up a dichotomy between inanimate matter and animate spirit that lifts humans above creation and turns the rest of the world – from animals and plants to soil and water – into “resources” to be used. Unfortunately this vision has given shape to the Business as Usual story we participate in today.

By shifting perception from an isolated, human-centered worldview to one that honors the spirit within all living things, we can access a deeper, animist-inspired understanding of interdependence. This expanded awareness fosters empathy, reverence, and responsibility toward the natural world.

The Work That Reconnects invites individuals to cultivate a similar reverence and sense of kinship with the Earth. Rooted in systems thinking and inspired by Buddhist concepts of interconnectedness, Joanna Macy’s work incorporates animist traditions in its recognition of the living, interconnected nature of existence. It seeks to restore relationships between individuals, communities, and the more-than-human world, helping people to heal disconnections and remember their place within the larger ecological web.

“Animism is not a religion one can convert to but rather a label used for worldviews and practices that acknowledge relationships between nature and the animal world that have power over humans and must be respected.

These practices […] can also be forms of environmental care, farming practices or protests, such as those conducted by water protectors [around the world]. New Zealand’s 2017 act recognizing the Whanganui River as a legal person, the culmination of decades of Maori activism, could be described as animism taking a legal form.

Animist practices are as variable as the peoples and places engaging in such relationships.” [1]